FridayReflection

23rd June 2023

Graham Tomlin describes

How to escape

'the sole cause of unhappiness'

Our capacity to distract ourselves from the bigger questions

is nothing new. Born 400 years ago this month, Pascal noted

something similar and that got him thinking.

Graham Tomlin tells his story. (edited)

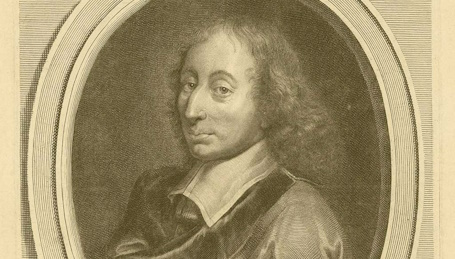

Blaise Pascal almost raises an eyebrow at today's distractions.

A recent survey of belief in Britain yielded a confused result.

Belief in God has declined, yet belief in the afterlife has risen.

People are less likely to see themselves as religious, and don't

pray much, yet continue to trust religious organisations.

We are caught between belief and unbelief.

A guide to our times might just be found in one of the greatest geniuses

of the modern world, born 400 years ago this year - on 19th June.

Blaise Pascal died before he reached the age of 40, and lived much of

his life in chronic sickness, but in less than four decades he became

one of the most famous and celebrated minds in France.

Born into a fairly conventional Catholic family and yet in time they came

under the influence of an intensely devout movement in 17th century

French religion, the Jansenists.

Blaise himself had a somewhat distant relation to the Jansenists,

being much more interested in his investigations into physics,

geometry and mathematics that began to raise eyebrows all over Europe.

That was until a dramatic event on the 23rd November 1654.

Not much is known about this life-transforming experience,

but for two dramatic hours late that evening, Pascal experienced

a profound encounter with the God who had always been vaguely

in the background of his life but not a compelling presence.

The change was radical if not total.

He didn't give up on the life of the mind, but instead started to think

deeply about how to change the minds of the many cultured despisers of

religion he had come to know through his scientific researches and

through his exposure to the fashionable salons of Parisian life.

Pascal had a problem in trying to do this.

He knew from his own experience that piling up arguments as to why

God might exist, or that you should think about God once in a while,

don't get you very far.

They tend to produce at best a lukewarm, distant kind of religion that

is more of a burden on the soul than a liberating presence.

They also point you towards the wrong God, the 'God of the philosophers',

a God who is the logical conclusion of an argument rather than a living,

breathing, haunting presence, both majestically distant and yet

hauntingly present at every moment.

As he put it, "the sole cause of a man's unhappiness is that he does not

know how to stay quietly in his room."

He would have marvelled at our age with Twitter, TikTok, 24-hour TV and

the myriad ways we find to divert ourselves during the most

fantastically distracted age there has ever been.

A betting man or woman would always bet on belief.

But Pascal knows that we don't think that way.

Why?

It's not because we are being rational;

it's because belief is inconvenient, we would rather there was no God,

it costs too much, and we just don't want to believe.

So if the evidence is inconclusive, and you're aware that your own motives

are mixed, then what do you do?

Pascal thinks we are creatures formed by habit.

So, his advice is to start living as if it's all true even if

you're not sure whether it is.

Start practising the habit of daily prayer to God even if you're

not sure whether he's listening or not.

Start treating each person you meet each day as if they're not just

another inconvenience in your path but someone precious,

loved by God and created in his image.

Start meeting with other Christians for that kind of mutual strengthening

of faith that only being with others can bring.

Take the bread and wine of Holy Communion as if they really are the gift

of Christs' presence to you. And see what happens.

Pascal reckons, sooner or later, as had happened to him and countless

others, belief will surely follow behaviour.

Start living as if it is true and slowly (or perhaps dramatically)

you will realise not only that it is true, but that it brings far more

joy and delight than you ever thought possible.

T.S. Eliot once wrote:

If we live in a culture that profoundly doubts God, yet which at the

same time longs to find happiness, then perhaps Pascal

is just the kind of guide we need.

Graham Tomlin is the Director of the Centre for

Cultural Witness and a former Bishop of Kensington.